August 21, 2006 – (Manila) – It was just a few years after the declaration of Martial Law when President Ferdinand E. Marcos, a master genius and high-caliber lawyer enacted single handedly with one stroke of his pen one of the country’s most important piece of legislature, the Labor Code.

Before May 1 of 1974, the Philippines didn’t have a cohesive law or policy with regards to the protection and welfare of the Filipino worker. What the country had were several pieces of laws or guidelines that were weak and often contradicting with each other, leaving a worker virtually stripped of his rights.

When Martial Law was imposed, Marcos had the legislature abolished and he, along side some of the finest legal minds of that time, he single handedly enacted laws, the framework of issues and concerns for a still very young Philippine Republic by virtue of a Presidential Decree.

Addressing the need of the workers, despite impressions and situations that made Marcos an unfriendly friend of the workers, the former president had a very clear intention, putting things into order and setting up systems for a young nation like the Philippines, something, that a bi-cameral congress from 1946 up to 1972 failed to enact into a law.

This entry is not about discussing issues on the relevance of a bi-cameral congress. This is not all about amending or changing the Constitution of this country, nor is it all about Marcos and that era. But briefly, let us look into Marcos’ handy work for the Filipino laborer.

It is in this writer’s view that though Marcos might have done several unacceptable things to this country and to its people, there are certain laudable actions that he did, that if he did not act on it, it would have resulted into chaos and among the better things he did was creating a law that comprehensively protected the rights and welfare of the Filipino worker.

In those years where demonstrations and rallies were suppressed by the Martial Law regime, the worker though given a set of guidelines on how they could demand for just wages, benefits and protecting their rights, could not actually voice their rights or actively seek redress for their unfair treatment at work.

Enacting a Labor Code during the time of Marcos was basically as a result of two things, (1) the need to conform with international standards on having labor laws and (2) to appease foreign investors in the country who wanted a clear guideline on how they will treat their workers.

Being an absolute power at that time, Marcos was able to put together the various pieces of legislations related to labor in the country from the time of the Spaniards, through the American period and the bits and pieces the Philippine legislature was able to put together and consolidate it into the Labor Code.

In the perspective of workers and the unions, this was a positive approach done my Marcos towards defending and protecting the rights of the workers but at the same time, it may be a law supposedly protecting them, it was also law that was used against the workers themselves.

Marcos expressly prohibited an active union movement in various companies at that time, especially in firms that Marcos had supposed ownership or in companies owned by his cronies.

If there was to be a union, it was more of a management union to gain recognition and it should be allied with trade unions that were created or approved by the administration.

Radicalism in the work place was easily demolished with the use of force if necessary and reason for this is that radicalism is a bane to investment.

The Machiavellian in Marcos painted a harmonious labor and business relations during his time, showing off statistics and figures, retelling of overly positive achievements in establishing peace in the labor force of this country.

By the time Marcos was already feeling the heat of his way out in 1986, from 1983 when his political opponent Benigno “Ninoy” Aquino was assassinated, an upheaval took place in this country and one of the most powerful fuel that eroded Marcos’ picture of harmony was the labor force.

In the view of Marcos, the noisiest from within the labor ranks are the ones who were influenced by the radical left and for Marcos who despised communism intensely, spared no courtesy or mercy in trouncing labor protesters who were obviously or tainted by the Reds.

By 1983, the Philippine labor force was in fact one of the biggest forces who filled the streets of the premiere business district in the then Municipality of Makati, the country’s “Wallstreet,” the 3 kilometer stretch of road called Ayala Avenue.

Work disruptions in the work place was a common thing in this period and productivity almost went to a complete halt, especially on Fridays when demonstrations against Marcos was at its peak.

When Corazon Aquino took power in 1986, with the promise of democracy in place, the labor force of this country was plagued with work stoppages and strikes, often illegal in nature plagued businesses as the country’s labor force demanded that their rights be heard.

In 1992, when Fidel Ramos took office, a sun shiny future in the platform called, “Philippines 2000,” was put into effect and the loud shouting in the streets of workers were finally drowned out with new investments, better job opportunities and more jobs.

At a given particular stage, the Philippines in the 90s was finally getting out of the muck and re-establishing itself as a power house economy, one of the emerging dragons of Southeast Asia.

From a purely agricultural economy, the Philippines was becoming a mixed agro-industrial economy and export driven with a very strong and growing local consumer sector. This was a sign that the Filipino was earning enough bucks to afford to buy and as the population continues to grow, more workers are waiting to join the country’s labor force.

As the country’s fortunes evolve as well as it’s business interests, the Labor Code of 1974, enacted single handedly by just one man remained as it was, un amended and with no improvements that was supposed to address the changing situations for the Filipino work force.

If there were any changes that affected the labor laws of this land, are some what we would call “stop gap” measures, little patches to solve specific problems and Congress’s political carrot to win laborers by offering legislated wage hikes which in a market economy is a stab into the heart of investors.

There have been plans to introduce legislated remedies, a comprehensive review and perhaps re-inventing the Philippine Labor Code to suit it to these modern times.

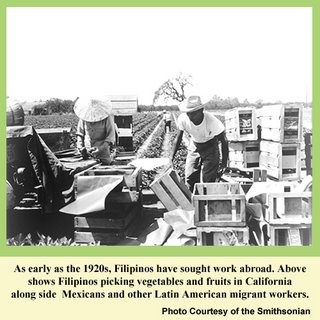

The Code that Marcos made did not foresee 8 million Filipinos working abroad, it did not foresee when the women of this country will be active in the labor force, work would be done at night or in a 24/7 cycle, rampant contractualization of workers, termination of workers before the prescribed 6-month probationary period and many other concerns that are now needed to be addressed and included in the country’s labor laws.

The two chambers of Congress has attempted to convene a Labor Commission to review and address the ever changing concerns of labor in this country but like the events we see in the political landscape of this country, the Labor Commission has gone through three Congressional sessions (it started at the time when Ramon Mitra, Jr. was still Speaker of the House and Jovito Salonga was Senate President and a woman named Gloria Arroyo was just an Undersecretary for Trade and Industry) and it has not made any significant contributions to amend the Labor Code.

The Employer’s Confederation of the Philippines or ECOP called on the Arroyo administration to spearhead efforts to amend or update the Philippine Labor Code by establishing a work-based population management program and the protection of workers in the informal sector.

Introducing a population management program as a work-related incentive for workers sound noble and reasonable, but it is not quite logical since this country has a population program in place (though needing amendments) but the problem is, government complains that it does not have funds to implement it and secondly the government cowers before the Roman Catholic Church who does not see the implication of a 2.5% annual growth rate in this country’s population.

In the case of introducing protection for those working in the informal sector, this is something that urgently needs attention and this is something that could be done quite easily if only we have a legislative branch that is not too pre-occupied with too much politics.

Noble ideas is not far and few for many in this country and the labor force of the Philippines do need the stimulus, the support and the protection it truly needs in order to make this country world class but above everything else, there should at least a degree of a genuine political assertiveness and will as well as focus in order to make things happen.

The Labor Code needs not only a few tweaking but it needs a general overhaul to make it relevant to these times.

* * *

No comments:

Post a Comment